Beyond Punishment

Traditional discipline asks: What rule was broken? Who did it? What punishment do they deserve? Restorative practices ask: Who was harmed? What do they need? Whose responsibility is it to make things right?

When Malik shoved another student in the hallway, the standard response would be suspension. Instead, he sat in a circle with the student he hurt, a facilitator, and both students' parents. He heard how his actions affected the other student. He explained the frustration that led to his outburst. Together, they agreed on how Malik would make amends—and what support he needed to handle frustration differently.

This is restorative practice: addressing harm by bringing together those affected, focusing on accountability and repair rather than punishment. Rooted in indigenous justice traditions and developed through criminal justice reform, restorative practices have increasingly found their way into schools as an alternative to exclusionary discipline.

The Philosophy of Restoration

Restorative practices rest on several key principles:

Harm Creates Obligations

When someone causes harm, they have an obligation to repair it. This isn't about suffering punishment but about taking responsibility for the impact of one's actions and making things right.

Those Affected Should Be Involved

The people affected by harm—victims, offenders, and community—should all have voice in addressing it. Decisions made about them should include them.

Relationships Are Central

Wrongdoing damages relationships. True resolution requires repairing those relationships, not just imposing consequences. Punishment often further damages relationships; restoration rebuilds them.

Community Matters

Incidents affect not just individuals but the broader community. Restorative processes involve the community in addressing harm and strengthen community bonds in the process.

Restorative Practices Continuum

Restorative practices range from informal to formal:

Affective Statements (Informal)

Adults expressing feelings about student behavior: "When you talk while I'm teaching, I feel frustrated because I can't help everyone learn." Uses "I" statements to communicate impact without blame.

Affective Questions

Questions that help students reflect: "What happened? What were you thinking? Who was affected? What do you need to do to make things right?" Guides students toward understanding impact and accountability.

Community Circles

Structured conversations where participants sit in a circle and pass a talking piece. Used for community building, academic discussion, or addressing classroom issues. Builds relationships proactively.

Restorative Conferences (Formal)

Facilitated meetings bringing together those who caused harm and those affected to address specific incidents. Results in agreements about how to repair harm and prevent recurrence.

Community Circles in Practice

Circles are the foundation of restorative school culture. Regular use of circles builds relationships and skills that make restorative responses to conflict possible.

Circle Structure

All participants sit in a circle with no tables or barriers. A talking piece passes around; only the person holding it speaks. A keeper (facilitator) guides the process, asking questions and managing the flow. Ground rules (typically called "circle values") establish expectations for participation.

Circle Types

Community-building circles strengthen relationships through sharing and connection. Used regularly (weekly or more), they build the trust foundation that makes restorative responses possible.

Academic circles use the circle format for instructional purposes—discussing content, exploring questions, processing learning.

Responsive circles address issues that have arisen—classroom conflicts, community harm, difficult events affecting the class.

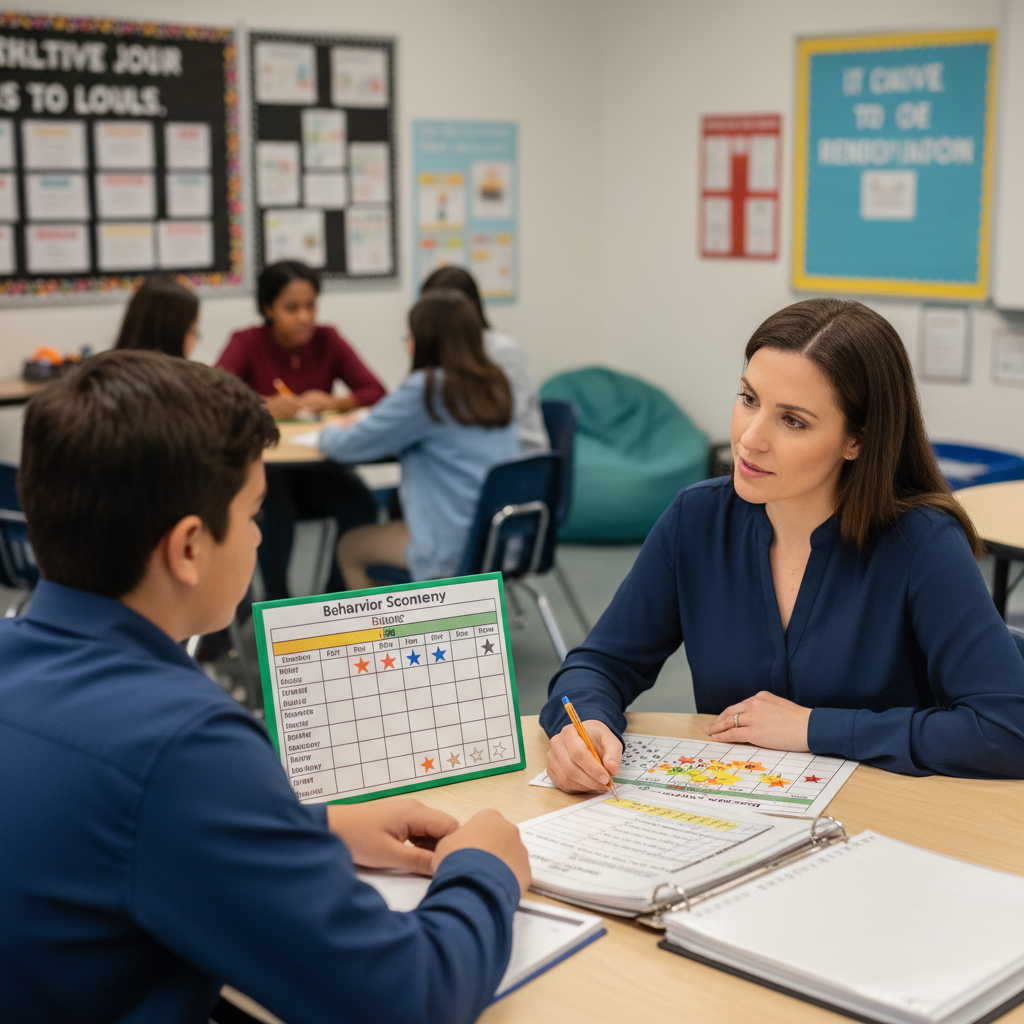

Behavior Management

Track behavioral incidents and implement positive behavior intervention strategies.

Restorative Conferences for Serious Incidents

When significant harm occurs, formal restorative conferences bring together those involved:

Preparation

The facilitator meets separately with all parties before the conference. They ensure participants understand the process, are willing to participate, and are emotionally ready. Participation must be voluntary; forced restorative processes aren't restorative.

Conference Process

The conference follows a structured script:

- • The person who caused harm describes what happened

- • Those affected share the impact on them

- • Supporters (parents, friends) share how they've been affected

- • Discussion of what needs to happen to make things right

- • Agreement on specific actions and timeline

Follow-Up

After the conference, follow-up ensures agreements are fulfilled. The process isn't complete until repair has actually occurred, not just been promised.

Sample Restorative Conference Questions

For the person who caused harm:

- • What happened?

- • What were you thinking at the time?

- • What have you thought about since?

- • Who has been affected by your actions?

- • What do you need to do to make things right?

For those affected:

- • What did you think when this happened?

- • How has this affected you?

- • What has been the hardest part?

- • What do you need to move forward?

Implementation Challenges

Implementing restorative practices isn't straightforward:

Time and Resources

Restorative processes take more time than traditional consequences. A suspension takes seconds to assign; a restorative conference takes hours. Schools need dedicated staff, training, and schedule flexibility.

Staff Buy-In

Some staff view restorative practices as "soft" or permissive. Changing mindsets requires ongoing professional development, evidence sharing, and patience as staff experience successful processes.

Skill Development

Facilitating circles and conferences requires specific skills. Brief training isn't sufficient; ongoing practice and coaching develop competence.

When It's Not Appropriate

Not every situation suits restorative approaches. When the person who caused harm isn't willing to take responsibility, when the person harmed doesn't want to participate, or when safety concerns exist, alternative approaches may be needed.

Evidence and Outcomes

Research on restorative practices shows promising results:

- • Reduced suspensions and expulsions

- • Decreased discipline disparities by race

- • Improved school climate

- • Higher satisfaction among participants in restorative processes

- • Lower recidivism compared to punitive approaches

However, implementation quality matters enormously. Schools that adopt restorative practices superficially—using the language without the philosophy—see minimal benefit.

Building Restorative Culture

True restorative practice isn't just a response to incidents—it's a school culture:

Proactive relationship building. Regular community circles build relationships and trust before conflicts occur. When students know and care about each other, they're less likely to harm each other and more capable of repair when harm happens.

Consistent philosophy. Adults model restorative approaches in their own interactions—with students and each other. The philosophy permeates the school, not just the discipline process.

Student empowerment. Students learn to facilitate circles and support peer conflict resolution. Restorative practices become something students own, not something done to them.

Family and community involvement. Families are partners in restorative processes, not just recipients of notification. Community members may participate in circles and conferences.

See AcumenEd in Action

Request a personalized demo and see how AcumenEd can transform your school's data.

Integration with Other Approaches

Restorative practices complement other frameworks:

PBIS integration. Restorative practices can be the Tier 2/3 intervention within a PBIS framework, or community circles can be a Tier 1 practice. The approaches share focus on positive school climate.

Trauma-informed alignment. Restorative practices align with trauma-informed principles: emphasizing safety, building relationships, providing voice and choice. Trauma-informed facilitators adapt processes for affected students.

SEL connection. Social-emotional learning builds the skills—empathy, self-awareness, responsible decision-making—that enable restorative participation. SEL and restorative practices mutually reinforce.

The Transformative Potential

Return to Malik. In a traditional system, his suspension would have communicated that he's bad, damaged his relationship with school, and done nothing to help him manage frustration differently. The student he harmed would have received no voice in the process and no genuine resolution.

In the restorative conference, Malik confronted the real impact of his actions. The other student shared his fear and hurt—humanizing the harm in ways that abstract consequences never could. Malik's parents learned about his frustrations; the school committed to supporting him. An agreement was reached that both students felt was fair.

This is what restoration can accomplish: genuine accountability, real repair, strengthened relationships. It's harder and slower than punishment. But it works better—for the student who caused harm, for those affected, and for the school community that holds them all.

Key Takeaways

- Restorative practices focus on repairing harm and rebuilding relationships rather than punishing rule violations.

- Practices range from informal (affective statements) to formal (restorative conferences), with community circles as the foundation.

- Implementation requires training, time, and culture change—superficial adoption produces minimal benefit.

- True restorative culture builds relationships proactively, not just addresses incidents reactively.

Marcus Johnson

Director of Data Science

Data scientist specializing in educational analytics with expertise in growth modeling and predictive analytics for student outcomes.