The Communication Lens

Behavior isn't random. When a student acts out, shuts down, or disrupts class, they're communicating something—a need, a feeling, a reaction to their environment. This doesn't excuse harmful behavior, but understanding its function is the key to changing it.

Marcus throws his worksheet on the floor and refuses to work. The traditional response might be immediate: a consequence for defiance, maybe removal from class, a call home. But what if we paused and asked: What is Marcus communicating?

Perhaps he can't read the worksheet and feels humiliated. Perhaps he's overwhelmed by problems at home. Perhaps he needs movement and has been sitting too long. Perhaps he craves attention and has learned that negative attention is better than none. Each possibility points toward a different response—one more likely to address the underlying issue rather than just suppressing the symptom.

This is the behavior-as-communication framework: understanding that challenging behavior serves a function for the student, and that lasting behavior change requires addressing that function, not just punishing the behavior.

The Four Functions of Behavior

Applied behavior analysis identifies four primary functions that challenging behavior typically serves:

Escape/Avoidance

The behavior helps the student get away from something aversive—a difficult task, an overwhelming environment, an uncomfortable social situation. Acting out in math class might be a way to get sent to the office and escape math.

Attention

The behavior gets attention from adults or peers—even negative attention counts. For students who feel invisible, disrupting class guarantees that someone notices them.

Access to Tangibles

The behavior helps the student get something they want—a preferred activity, an item, time with friends. A tantrum might historically have resulted in getting what they wanted.

Sensory/Automatic

The behavior meets a sensory need or feels good in itself—rocking, fidgeting, making sounds. This function doesn't require an audience; the behavior is self-reinforcing.

Most challenging behaviors fit into one or more of these categories. Identifying the function guides intervention: we can't effectively address escape-motivated behavior with strategies designed for attention-seeking behavior.

Why Function Matters

Consider two students who both disrupt class by calling out:

Student A calls out because she craves attention. When the teacher responds—even with a reprimand—she gets what she wants. The behavior is reinforced.

Student B calls out because he's anxious and needs reassurance. He's not seeking attention but managing internal distress. A public reprimand increases his anxiety, potentially making behavior worse.

Same surface behavior. Different functions. Different effective interventions.

For Student A, the intervention might be ignoring call-outs while giving positive attention when she raises her hand. For Student B, the intervention might be a private signal system that provides reassurance without public interaction.

When we respond to behavior without understanding function, we often accidentally reinforce the very behavior we're trying to stop—or make it worse through mismatched responses.

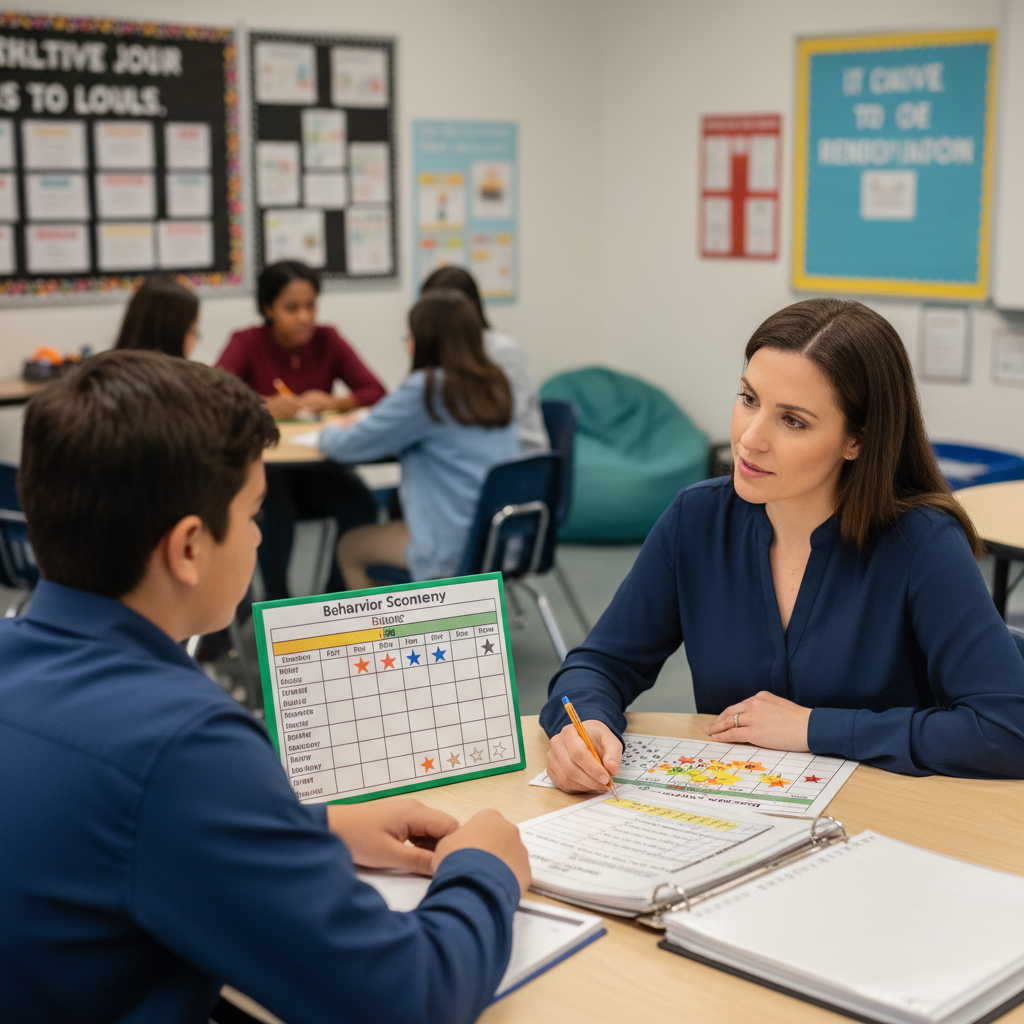

Behavior Management

Track behavioral incidents and implement positive behavior intervention strategies.

Identifying Function

How do we figure out what function a behavior serves? Several approaches help:

ABC Analysis

Track what happens before (Antecedent), during (Behavior), and after (Consequence) challenging behaviors. Patterns emerge: Does the behavior happen mostly during certain activities? What consequence typically follows? Over time, the function becomes clearer.

ABC Analysis Example

| Antecedent | Behavior | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Teacher assigns writing task | Marcus tears up paper | Sent to office (no writing required) |

| Independent reading time | Marcus walks around room | Teacher engages, redirects |

| Math worksheet distributed | Marcus puts head down, refuses | Teacher moves on, Marcus doesn't do work |

Pattern suggests: Behavior functions to escape difficult academic tasks. Marcus successfully avoids work he finds challenging.

Questions to Ask

When analyzing behavior, consider:

- • When does the behavior occur most often? (Time, setting, activity)

- • What typically happens right before the behavior?

- • What typically happens right after?

- • What does the student get or avoid through the behavior?

- • Does the behavior occur when the student is alone?

- • What would the student do if they could do anything?

Functional Behavior Assessment

For persistent or serious behavior challenges, a formal Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA) provides systematic analysis. FBAs typically include observation, interviews, review of records, and data analysis to identify behavior function and guide intervention.

Responding to Function

Once we understand what behavior communicates, we can respond more effectively:

For Escape-Motivated Behavior

If behavior functions to escape something aversive, address the aversiveness:

- • Modify tasks to appropriate challenge level

- • Teach coping strategies for frustration

- • Provide breaks before behavior occurs

- • Teach appropriate ways to ask for help or breaks

- • Ensure escape doesn't follow challenging behavior (when safe)

For Attention-Motivated Behavior

If behavior functions to get attention:

- • Provide frequent positive attention for appropriate behavior

- • Minimize attention for minor inappropriate behavior

- • Teach appropriate ways to get attention

- • Build relationship so student doesn't need to act out to connect

- • Consider peer attention, not just adult attention

For Tangible-Motivated Behavior

If behavior functions to get something wanted:

- • Teach appropriate requesting

- • Provide access to desired items/activities contingent on appropriate behavior

- • Don't provide tangibles following challenging behavior

- • Consider whether tangibles can be incorporated into instruction

For Sensory-Motivated Behavior

If behavior meets sensory needs:

- • Provide appropriate sensory alternatives

- • Build movement breaks into schedule

- • Allow fidgets or sensory tools

- • Consider sensory needs in environment design

- • Consult occupational therapy when needed

See AcumenEd in Action

Request a personalized demo and see how AcumenEd can transform your school's data.

Teaching Replacement Behaviors

Suppressing challenging behavior without teaching alternatives leaves students without ways to meet their needs. The key is replacement behaviors—appropriate ways to achieve the same function:

If Marcus tears up papers to escape overwhelming work, teach him to request help, ask for a break, or use a "pause" card. If the replacement behavior works as well as the challenging behavior, he'll use it. If it doesn't work, he'll return to what does.

Effective replacement behaviors are:

- • Functionally equivalent—they meet the same need

- • More efficient—they work faster or more reliably than the problem behavior

- • Teachable—the student can actually learn and use them

- • Socially acceptable—they work in real-world settings

The Limits of This Framework

Understanding behavior as communication is powerful but has limits:

Safety first. When behavior is dangerous, immediate safety response takes priority over functional analysis. Understanding why a student is throwing furniture matters—but stopping the throwing matters more in the moment.

Understanding isn't excusing. Recognizing that behavior serves a function doesn't mean the behavior is acceptable. The goal is changing the behavior—understanding function is the path to effective change, not a reason to tolerate harmful actions.

Some behaviors need additional expertise. Complex behavioral challenges may require consultation with behavior specialists, school psychologists, or mental health professionals. Classroom teachers shouldn't be expected to manage severe behaviors alone.

Context matters. Behavior doesn't occur in a vacuum. Trauma, mental health, developmental differences, and environmental factors all influence behavior. Functional analysis is one lens, not the only lens.

A Shift in Mindset

Adopting the behavior-as-communication framework requires a mindset shift:

From "Why is this student doing this to me?" to "What is this student trying to tell me?"

From "What consequence will stop this?" to "What need is this meeting?"

From "How do I make this behavior stop?" to "What skill does this student need to learn?"

This shift doesn't mean being permissive. It means being strategic—using understanding to drive effective intervention rather than reacting punitively to surface behaviors. It's harder than simply applying consequences, but it produces better results.

Return to Marcus. With the communication lens, we might discover his paper-tearing is escape from tasks he can't do. The intervention becomes academic support, frustration tolerance skills, and a break system—not just consequences for defiance. Marcus learns to manage his struggles. The behavior decreases. That's the power of understanding behavior as communication.

ABC Early Warning System

Identify at-risk students before they fall behind with our comprehensive ABC framework.

Key Takeaways

- All behavior serves a function—escape, attention, tangibles, or sensory needs—and identifying that function guides effective intervention.

- ABC analysis (Antecedent-Behavior-Consequence) helps identify patterns that reveal what behavior is communicating.

- Effective intervention requires teaching replacement behaviors—appropriate ways to meet the same need.

- Understanding behavior isn't excusing it—it's the path to more effective change than reactive punishment.

Dr. Sarah Chen

Chief Education Officer

Former school principal with 20 years of experience in K-12 education. Dr. Chen leads AcumenEd's educational research and curriculum alignment initiatives.